Sweet Home, Oregon – A wrongful death lawsuit filed by the family of a 73-year-old military veteran who relied on a motorized wheelchair has been settled after allegations that construction workers allowed him to pass through a work zone, leading to a fatal fall into a trench. The case centered on whether contractors and state agencies failed to properly protect or redirect a vulnerable pedestrian during an active construction project.

What happened at the Sweet Home construction site

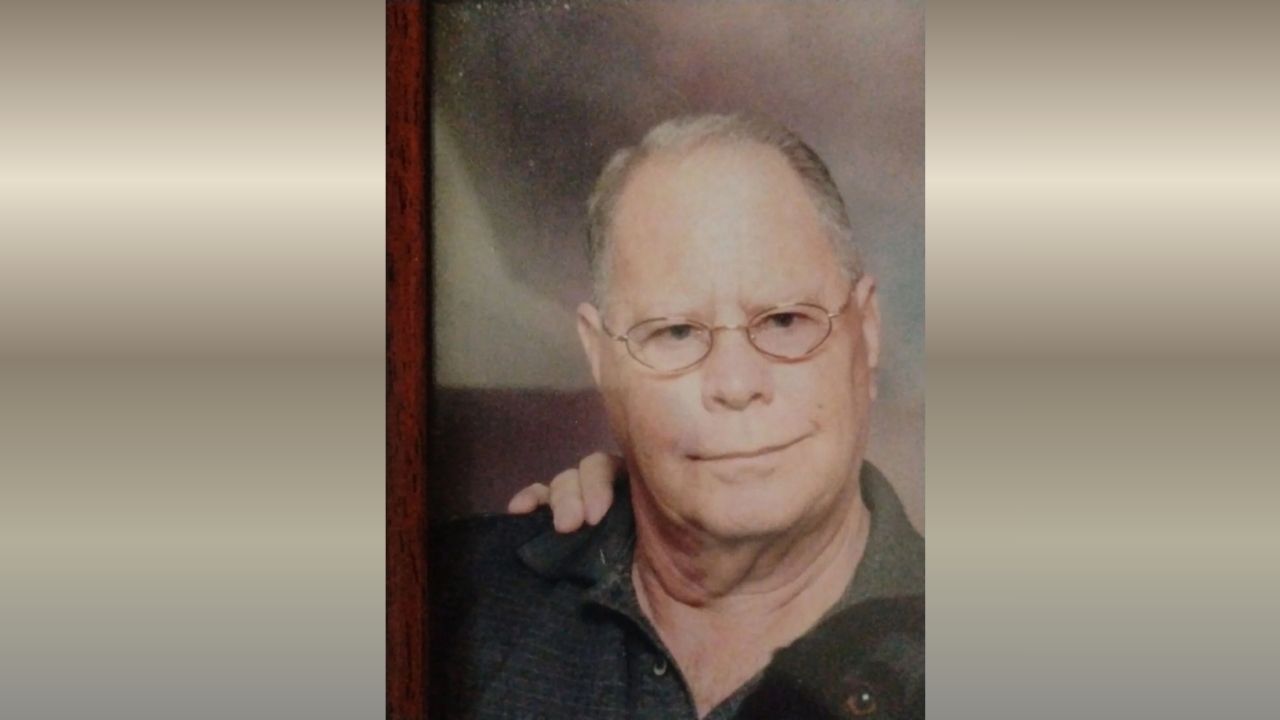

The incident occurred in 2022 at the intersection of 18th Avenue and Main Street in Sweet Home. According to the lawsuit, Carl Wescott, a wheelchair-bound veteran, was returning home from a nearby store when he encountered an active construction area managed by county contractors.

Court documents state that Wescott had earlier crossed through the same construction zone without incident after workers allegedly allowed him to pass. On his return trip, his family claims that an employee moved a piece of heavy equipment to create a path for him to cross the closed intersection again.

During this attempt, Wescott fell into an open trench, suffering catastrophic injuries.

Severe injuries and final days in the hospital

The lawsuit details extensive trauma resulting from the fall. Wescott suffered:

- An open ankle fracture-dislocation

- A fractured left fibula

- A fractured left upper arm bone

- Damage to muscles, tendons, ligaments, nerves, and soft tissue across his head, neck, shoulders, back, hips, and legs

The complaint describes that Wescott spent his final days hospitalized, stating that he “spent his final days in a hospital bed.”

Two weeks after the incident, Wescott died from complications related to his injuries.

Preexisting health conditions cited in lawsuit

Wescott’s family acknowledged in court filings that he had several underlying medical conditions prior to the fall, including kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, and diabetes. They argued, however, that the injuries sustained in the construction trench directly contributed to his rapid decline and death.

Companies and agencies named in the lawsuit

The wrongful death lawsuit named multiple defendants involved in the construction project. These included Lane County contractors:

- Wildish Construction, based in Eugene

- C-2 Utility Contractors, based in Coburg

- Lantz Electric, based in Eugene

The state of Oregon was also named as a defendant.

According to the family, the construction site lacked adequate safeguards for pedestrians with disabilities and failed to provide a safe, accessible detour route.

Contractors deny responsibility

Court documents reviewed by the Albany Democrat-Herald and its sister publication, the Corvallis Gazette-Times, show that the contractors denied liability.

C-2 Utility Contractors argued that Wescott was negligent and responsible for his own injuries. Lantz Electric similarly denied fault, stating that Wescott had allegedly been instructed not to reenter the construction zone and was told to use an alternate route instead.

State officials also contended that Wescott bore responsibility for the incident.

Disputed accounts of what workers told Wescott

A central issue in the case was whether construction workers explicitly allowed Wescott to pass through the closed intersection. The family claimed he was waved through and assisted by workers, including the movement of a backhoe to clear his path.

The defense disputed this version of events, asserting that Wescott ignored instructions and entered a restricted area against warnings.

No trial testimony was heard, leaving these conflicting accounts unresolved in court.

Settlement reached before trial

The case was scheduled for trial in May 2026, but it was settled earlier this month. A Linn County court formally dismissed the lawsuit on December 19, according to online court records.

The terms of the settlement have not been disclosed. Wescott’s family had been seeking $2.35 million in damages.

Broader safety concerns around construction zones

The lawsuit highlights ongoing safety concerns for pedestrians, particularly seniors and people with disabilities, around active construction sites. Advocacy groups have long warned that poorly marked detours, open trenches, and inconsistent worker guidance can pose serious risks to wheelchair users and others with mobility challenges.

Federal and state guidelines generally require construction zones to maintain accessible pedestrian routes or provide clearly marked, safe alternatives. Whether those standards were met in this case remains a point of contention.

Conclusion

While the settlement closes the legal case surrounding Carl Wescott’s death, it leaves unanswered questions about responsibility and safety practices at construction sites. For his family, the outcome represents accountability without public answers, and for communities, it underscores the potentially fatal consequences of inadequate protections for vulnerable pedestrians.

Share your experiences or thoughts on pedestrian safety near construction zones in the comments below.